While the Emory-Grady partnership provided, in one administrator’s words, “abundant clinical material,” Emory University School of Medicine struggled mightily for decades to overcome economic obstacles—namely, the inability to pay clinical faculty. By 1940, in the wake of the Great Depression, the medical school relied primarily on the volunteer efforts of local doctors. “I don’t know what we can do about medical school costs,” wrote university leader Robert Mizell to a trustee. “I don’t see how we can go ahead, yet I know we can’t afford to turn back.”

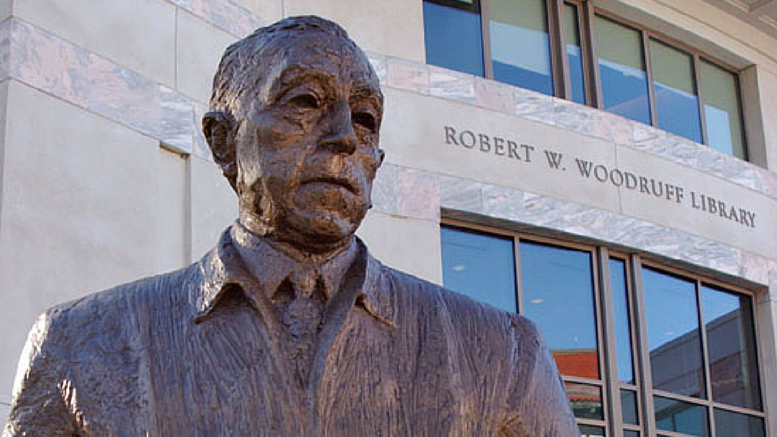

In the mid-1940s, with the medical school on the verge of financial collapse, famed Coca-Cola President Robert Woodruff stepped in. Woodruff decided to personally take on the school’s deficit—covering annual losses as high as $400,000 out of his own pocket. In 1953, with Woodruff’s backing, physician faculty formed the Emory Clinic, a medical practice plan to give the school financial autonomy.

The Emory Clinic plan worked as follows: medical faculty would teach at least one day per week. On non-teaching days, they would work in the clinic, donating a portion of clinic revenues to cover operational costs and support academic expenses. Contributions from the clinic grew steadily, and its structure allowed the medical school to recruit the growing number specialists and sub-specialists needed for state-of-the-art patient care.

Emory continued to gain traction in the medical community. In addition to Grady Memorial Hospital, Emory medical students were eventually assigned to Wesley Memorial Hospital, Lawson General Hospital (now Atlanta VA Medical Center), and Crawford Long Hospital (now Emory University Hospital Midtown). Later yet, the school would assume responsibility for patient care at Egleston Hospital and the Wesley Woods Center, broadening Emory’s medical curriculum to encompass the full spectrum of care, from pediatrics to geriatrics.

For most faculty members and students, however, the soul of the medical school remained at Grady, where Emory first cultivated its reputation for clinical education. Because of this, Emory’s expansion efforts, including the Emory Clinic, were initially met with some resistance.

Despite Grady’s financial struggles as a public hospital, Emory faculty members—including J. Willis Hurst, a founding member of the clinic and one of Grady’s strongest supporters—remained staunch advocates of Emory at Grady, emphasizing the hospital’s unrivaled educational opportunities as well as their personal commitment to Grady patients. This unwavering dedication ultimately sustained the partnership: Emory’s leaders concluded that the interests of Emory and Grady are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they are interdependent. After all, Atlanta can’t live without Grady.

Related Links/Sources

• The Legacy of Emory at Grady: Grady Memorial Hospital

• Raising the Bar: 150 Years of a Medical School in Motion

• Grady Health System

• Emory University School of Medicine

• Emory University Department of Medicine

• Jordan Messler’s April 2015 presentation at Medicine Grand Rounds

• A Marriage Made in Atlanta

• Emory at Grady